flowchart LR

mu["Language of impression: perception"]

i["Internal state: meaning"]

tau["Language of expression: action/output"]

mu --> i --> tau

The Idiolectic View

The Idiolectic View - Private Languages of Impression and Expression

machine-learning influenced

Disclaimer — Work in Progress

The following text presents an evolving conceptual framework—the Idiolectic View—which explores the individually constructed nature of language, meaning, and communication. It should be read as a philosophical and methodological reflection in development, not a finalized theory.

Language is not a shared code, nor a system of universally interpretable signs; rather, it emerges from the interaction between a perceiving, embodied individual and the world. The Idiolectic View holds that language is part of knowledge, and since all knowledge is individual (following Józef M. Bocheński), so too must language be individual. This foundational insight explains why reading can inspire thoughts beyond what an author intended, why miscommunication is ubiquitous, and why change is often so difficult—because meaning stabilizes within a person over time, forming internal structures that resist reconfiguration.

At the heart of the concept are two distinct but interacting systems: a private language of impression and a private language of expression, each representing one direction of the individual’s engagement with the world. Together, they make up an individual's idiolect—a personal, calibrated system for interpreting and influencing the world.

Let us define the core elements:

𝑒: A present external stimulus—everything currently available to perception, including visual, auditory, tactile, and other sensory input. It is the world, encountered moment-to-moment.

𝜇: The mapping from external to internal; a language of impression, through which external stimuli are internalized into structured, private meaning (we listen to the world).

𝜏: The mapping from internal to external; a language of expression, through which internal states are externalized into behavior, posture, gesture, sound, or speech (we make the world listen).

𝑖: An internal representation—meaning, latent, and formed through repeated applications of 𝜇.

Crucially, the passing of time is not an input in the same way as sensory data. It is the medium of differentiation, the driver of entropy, and the field of calibration. It is what makes change, variation, error, memory, and learning possible. Meaning arises not in an instant but through time, as mappings are shaped, reinforced, or disrupted by unfolding experience. Without time, there is no sequence, no structure, and no possibility for calibration.

The question of feedback reveals the central philosophical move of the Idiolectic View. What counts as feedback is not a property of the world, but a judgment constructed internally. The world provides stimuli—𝑒—but it does not label them as feedback. It is only through the language of impression 𝜇 that an individual recognizes a meaningful relation between a prior expression and a later perception. That recognition is itself an internal process. The same event may or may not be seen as feedback depending on whether it is interpreted as a consequence of one’s action. Feedback, then, is not a kind of input, but a product of interpretation. It is the reflective loop within the idiolect, through which expression and impression are realigned.

It rests on the following assumption: Primacy of impression; The capacity to internalize external stimuli (𝜇) is logically and temporally prior to the ability to express (𝜏). Without a capacity to perceive and differentiate, there is nothing to express. Even early, nonverbal outputs like crying presuppose an internalized state—pain, discomfort, feeling of existence—formed through perception.

A note here: Suppose an “abstract language” exists. Either:

It is purely rational: then there could be only one such language, no variation, no misunderstanding—clearly false empirically. One might argue for a plurality of rational languages, but this still fails to explain why they should be finite, and not as many as there are individuals—at which point we arrive at the notion of a private language. That possibility, however, falls outside this discussion.

It is empirical: then it must be transmitted and learned, requiring an already-operational 𝜇 in every learner.

Therefore, external→internal capacity is prior to any language. And when it is, no abstract language is possible, because it is always interpreted through an individual’s internal system 𝜇. The same symbol will link to different underlying concepts in different individuals. As the number of human beings is potentially unlimited, so is the number of possible mappings between signals and meanings.

The model mirrors encoder–decoder architectures in machine learning. The impression mapping 𝜇 functions as an encoder: it transforms external signals into latent, structured internal representations. The expression mapping 𝜏 is a decoder: it takes internal states and generates outward signals, shaped to achieve specific effects. Alignment does not require shared labels.

A newborn’s cry illustrates this process. The cry is not yet about anything in particular. It is a default output—an undifferentiated signal produced by an untrained expressive system. Over time, events following certain cries are interpreted, by the child’s 𝜇, as consequences of those cries—and become the basis for future expressive refinement. Feedback, in this case, is not what happened, but what is perceived to have happened because of the cry.

This architecture also explains the resistance to change. Once 𝜇 and 𝜏 stabilize through interpreted experience, they become difficult to reconfigure. New events must pass through entrenched internal mappings. As a result, reinterpretation and relearning become effortful. This is not merely cognitive inertia—it is the friction of revising meaning structures deeply integrated into an individual’s perceptual and expressive history.

Finally, this view exposes a structural contradiction in universal language theories. If meaning arises through 𝜇, and if 𝜇 is individually constructed, then expression via 𝜏 must also be individual. No fixed expressive code can function universally or abstract, because all symbols are formed and interpreted through private mappings. Either a language is purely rational and invariant—in which case misunderstanding should be impossible—or it is empirical and learned, in which case it must pass through 𝜇, and thus lose its universality.

Idiolect calibration occurs when an individual assesses whether their perception of external stimuli after the expression aligns with their original expressive intent; if the two are consistent, no adjustment is made. communication, then, is the special case where this calibration takes place, as captured in the formula below.

\[ \mu_a(\tau_b(\mu_b(\tau_a(i)))) \sim \mu_a(\tau_a(i)) \]

Where \(\mu_a\) and \(\mu_b\) are the internalization (language of impression) mappings of agents A and B, and \(\tau_a\), \(\tau_b\) are their expression mappings (language of expression). The relation \(\sim\) denotes that the result is judged by A to be consistent with their intended expression—not necessarily identical in content or form, but sufficient not to warrant a revision of \(\tau_a\). \(\tau_a(i)\) results in modification of \(e\).

The Idiolectic View is inspired by the architecture of CycleGANs: two systems, each with their own internal mappings from input to output, learn to translate between domains without needing paired examples or shared symbolic codes. Human communication functions similarly. No shared language or convention is required—only exposure to sufficiently similar environment, passing of time, and the shared physical architecture of human bodies. Importantly, the language of expression encompasses all forms of action, not just verbal output. For this reason, the construction of an idiolect does not require interaction with other humans; exposure to the environment alone is sufficient. Interaction with humans just alters \(\mu\) to make useful observations about other’s intents, and \(\tau\) allows to make useful expressions, including what is conventionally labeled “language”, though this label captures only a narrow subset of expression.

This also explains how we are able to read the works of people long dead. Our idiolects, shaped by similarly structured environments and similarly embodied faculties, are capable of approximating symbolic patterns preserved in writing. The books themselves do not contain meaning in any internal sense—they do not carry an author’s internal state \(i\). What they preserve is a pattern of expression—a sequence of symbols once produced by the author’s expression mapping \(\tau\). We make sense of these symbols not by retrieving meaning, but by reconstructing it: we interpret them through our own language of impression \(\mu\), guided by overlapping structures of experience. Communication across time, then, is not transmission—it is partial reconstruction.

One thing often strikes me: neither language—ultimately—nor our cognitive faculties exist for understanding in itself. They exist for our adaptation to conditions, for survival and development. To conceive of language as anything more than a tool in this evolutionary and existential process is a misunderstanding. The path may be long, the means complex, but the end—whether for the individual, the group, or the species—is always the same: continuity, adaptation, and growth. Language is, in this view, a practical instrument.

And like all such instruments, language is subject to power. Those in positions of authority find ways to shape both the language of expression and the language of impression in those who are not. Suppressing actions through law, for instance, alters the language of expression—this is overt. The individual perceives negative consequences for specific expressions and, over time, learns to self-regulate. But the deeper and more lasting form of control lies in shaping the language of impression: the very apparatus by which individuals form internal states and construct meaning.

When the formation of the language of impression is subtly and efficiently altered, individuals unconsciously construct the limits of their own expression. They begin to speak, act, and even think within boundaries that were not chosen, but implanted—adhering to the will of those who engineered the structure of perception itself. This is where the true power resides: not only in what is allowed to be said (as this comes later), but in what can be seen, felt, and known in the first place.

set.seed(42)

# Define the "real" objects in the environment

objects <- c("apple", "banana", "cat")

create_agent <- function(objects, vocab_size = 10) {

# Randomly assign a perceptual embedding (e.g., numeric vectors)

mu <- setNames(lapply(objects, function(x) runif(3)), objects)

# Create τ: randomly assign symbols from a shared pool

symbols <- paste0("s", 1:vocab_size)

tau <- setNames(sample(symbols, length(objects), replace = FALSE), objects)

list(mu = mu, tau = tau)

}

agent_A <- create_agent(objects)

agent_B <- create_agent(objects)simulate_exchange <- function(i, agent_A, agent_B) {

# A: perceive → express

mu_A_i <- agent_A$mu[[i]]

symbol <- agent_A$tau[[i]]

# B: receive symbol → infer object

obj_B_candidates <- names(agent_B$tau)[agent_B$tau == symbol]

if (length(obj_B_candidates) == 0) {

return(NA) # B doesn't recognize the symbol at all

}

obj_B <- obj_B_candidates[1] # Assume one best guess

inferred_mu_B <- agent_B$mu[[obj_B]]

# A: re-interpret B’s response (assume B expresses obj_B again)

symbol_B_back <- agent_B$tau[[obj_B]]

obj_A_candidates <- names(agent_A$tau)[agent_A$tau == symbol_B_back]

if (length(obj_A_candidates) == 0) {

return(NA) # A cannot interpret B's return symbol

}

obj_A_back <- obj_A_candidates[1]

mu_A_recon <- agent_A$mu[[obj_A_back]]

# Similarity (cosine)

sim <- sum(mu_A_i * mu_A_recon) / (sqrt(sum(mu_A_i^2)) * sqrt(sum(mu_A_recon^2)))

return(sim)

}

simulate_alignment <- function(agent_A, agent_B, rounds = 20) {

sims <- matrix(NA, nrow = rounds, ncol = length(objects))

colnames(sims) <- objects

for (r in 1:rounds) {

for (obj in objects) {

sim <- simulate_exchange(obj, agent_A, agent_B)

sims[r, obj] <- sim

# If miscommunication, adjust B’s τ to match A’s (basic alignment mechanism)

if (is.na(sim) || sim < 0.9) {

agent_B$tau[[obj]] <- agent_A$tau[[obj]]

}

}

}

return(list(similarity_matrix = sims, final_A = agent_A, final_B = agent_B))

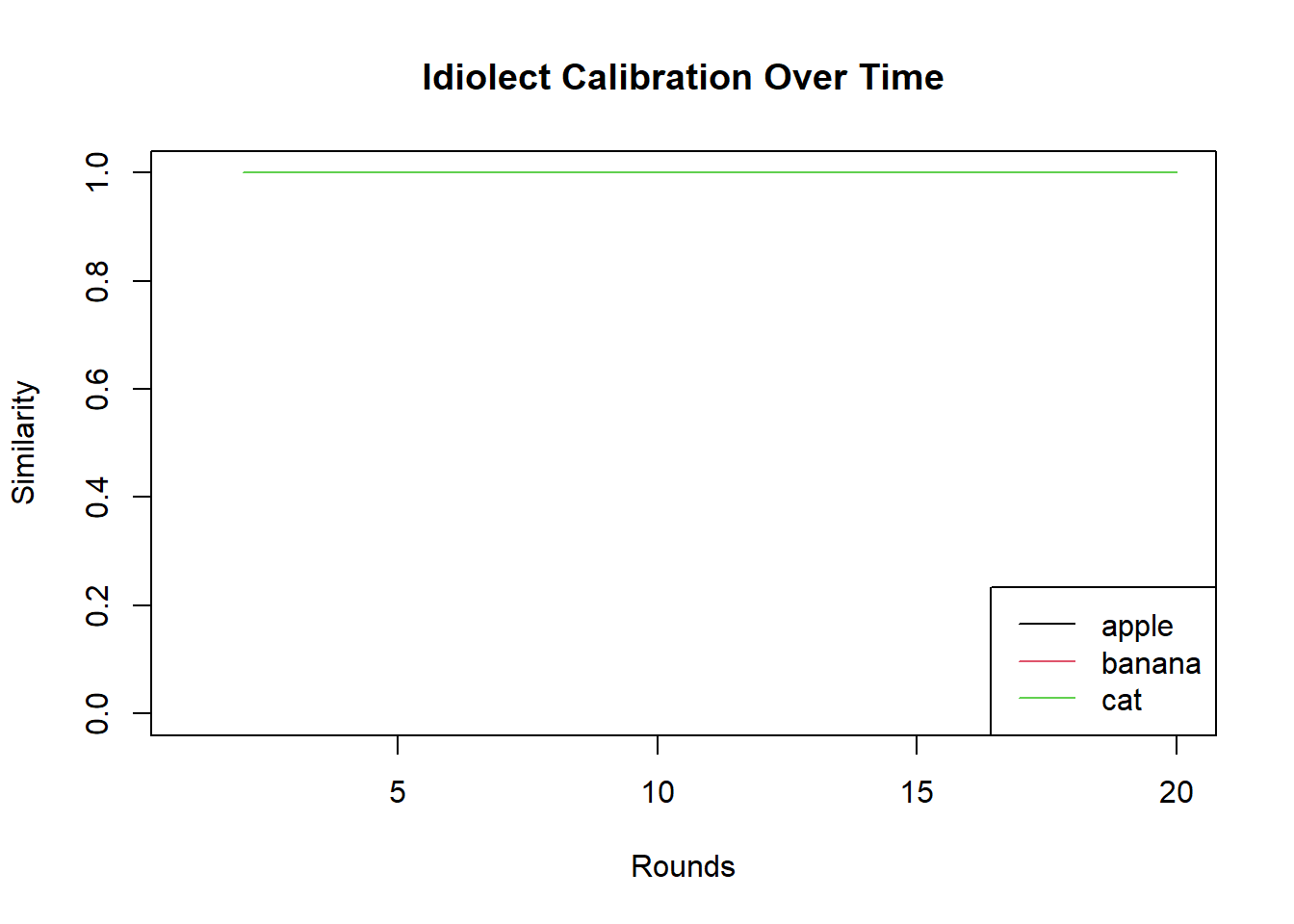

}result <- simulate_alignment(agent_A, agent_B)matplot(result$similarity_matrix, type = "l", lty = 1, col = 1:3,

xlab = "Rounds", ylab = "Similarity", main = "Idiolect Calibration Over Time",

ylim = c(0, 1))

legend("bottomright", legend = objects, col = 1:3, lty = 1)